用两天琢磨一道题

前面还在沾沾自喜我写出来的脚本运行效率战胜了参考答案,但这道题目我是看着参考答案都不知道他们在说什么。如果只是一个词,我的确可以列举出它一次减少一个字母可以出现的所有可能,但怎么知道上一层可能和这一层的哪个配套???我花了2天时间去研究、消化答案。一边搞清楚答案为什么这样,另一边考虑有没有其它容易吃透的表达方式。这道题之所以让我非常纠结,根本的原因是我想不透到底我可以用什么手段实现。没有可以实现的逻辑,就不会有可行的编程。

Exercise 4: Here’s another Car Talk Puzzler (http://www.cartalk.com/content/puzzlers): What is the longest English word, that remains a valid English word, as you remove its letters one at a time? Now, letters can be removed from either end, or the middle, but you can’t rearrange any of the letters. Every time you drop a letter, you wind up with another English word. If you do that, you’re eventually going to wind up with one letter and that too is going to be an English word—one that’s found in the dictionary. I want to know what’s the longest word and how many letters does it have? I’m going to give you a little modest example: Sprite. Ok? You start off with sprite, you take a letter off, one from the interior of the word, take the r away, and we’re left with the word spite, then we take the e off the end, we’re left with spit, we take the s off, we’re left with pit, it, and I. Write a program to find all words that can be reduced in this way, and then find the longest one. This exercise is a little more challenging than most, so here are some suggestions: You might want to write a function that takes a word and computes a list of all the words that can be formed by removing one letter. These are the “children” of the word. Recursively, a word is reducible if any of its children are reducible. As a base case, you can consider the empty string reducible. The wordlist I provided, words.txt, doesn’t contain single letter words. So you might want to add “I”, “a”, and the empty string. To improve the performance of your program, you might want to memoize the words that are known to be reducible. Solution: http://thinkpython2.com/code/reducible.py.

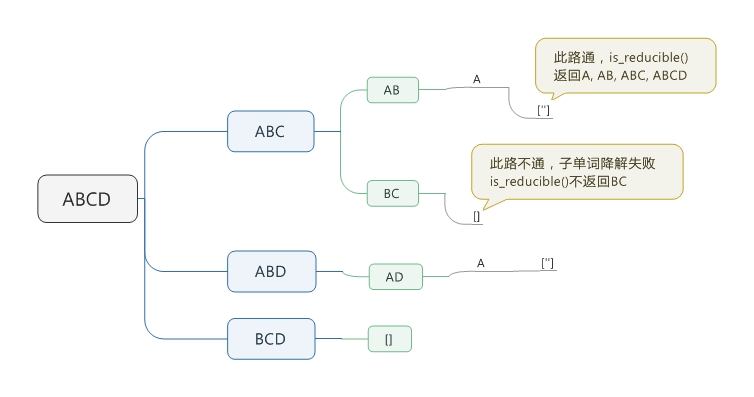

最终,我觉得自己总算消化了,顺便画了个思维导图帮助大家理解到底分解到什么程度叫做完成,什么状态叫做分解失败。[”]和[]是两种不同的东西!!!!!!

is_reducible()是最关键的函数,memos用在这里,memos初始设置了known[”] = [”]也很关键,这是个守卫模式,没有守卫is_reducible()根本没法玩。这个脚本里的5个函数,除了一开始的创建字典函数,其余函数都可以单独测试,把一个固定单词放进去脚手架测试,可以帮助理解。cut_letter(),is_reducible()和all_reducible()这三个函数最终返回的都是列表,它们的样式都是类似的。希望我理解过程中的注释能帮助到有需要的人。PS一句:参考答案的打印效果让人很晕,我修改版的打印效果很美丽:)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 | from time import time def set_dict(fin): d = {} for line in fin: word = line.strip() d[word] = 0 for word in ['a', 'i', '']: d[word] = 0 return d def cut_letter(word, d): # 生成子单词,返回列表 l = [] for i in range(len(word)): new_word = word[:i] + word[i+1:] if new_word in d: l.append(new_word) return l # ['']长度为1,[]长度为0,无子词不能分解时返回[],'a'返回[''] def is_reducible(word, d): # 判断能否生成无限子单词,返回列表 if word in known: # 守卫模式下,''空字符串被列入初始字典,不列入永远会被递归到[],无果 return known[word] # if word == '': # 不用memos的时候,需要加入这句守卫 # return [''] l = [] for new_word in cut_letter(word, d): if len(is_reducible(new_word, d)) > 0: l.append(new_word) known[word] = l return l def all_reducible(d): # 收集所有无限子单词的单词,返回列表 l = [] for word in d: if len(is_reducible(word, d)) > 0: # 有列表,即有无限子单词 l.append((len(word), word)) # 列表含有N个元组,元组里有2个元素,1为单词的字母数量,2为单词本尊 new_l = sorted(l, reverse = True) # 每次减少一个字母,单词的字母越多当然就能降解出越多层了 return new_l def word_list(word): # 打印单词及子单词 if len(word) == 0: # 最后一个进入is_reducible()的是[''],对应l[0]为无,打印结束 return print(word) l = is_reducible(word, d) # 因为是被鉴定过词汇表里的词,所以必定有无限子单词 word_list(l[0]) # 子单词有多个时只选第1个 known = {} # memos实际上只在is_reducible()起作用,除了提高效率,还能用作守卫 known[''] = [''] # 因为is_reducible()返回的是列表,所以即便是空字符串,键值也必须是列表! fin = open('words.txt') start = time() d = set_dict(fin) # 普通的字典,键为单词,键值为0 words = all_reducible(d) # 列表,元组,2元素 for i in range(5): word_list(words[i][1]) # 列表里第某个元组的第2个元素 end = time() print(end - start) # complecting # completing # competing # compting # comping # coping # oping # ping # pig # pi # i # twitchiest # witchiest # withiest # withies # withes # wites # wits # its # is # i # stranglers # strangers # stranger # strange # strang # stang # tang # tag # ta # a # staunchest # stanchest # stanches # stances # stanes # sanes # anes # ane # ae # a # restarting # restating # estating # stating # sating # sting # ting # tin # in # i # 0.6459996700286865 # 无memos 1.5830001831054688, 有memos 0.6459996700286865 |